Around two sixteenth-century doors in Évora and their musical context1

❧

The door, an object of everyday life frequently forgotten, has, in certain contexts, some historical significance, sometimes not by itself, but by the individuals who used them. The present text does not intend to be a philosophical exercise on the symbolism of the door, notably through its biblical readings, so associated with sacred art, but to propose a contextual approach taking as a starting point two examples in which this object appears as an object of everyday life of several of the musicians that distinguished themselves, not only locally in Évora’s music, as well as in the panorama Portuguese music, notably in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This text therefore proposes a brief reflection on these two contexts which, although distinct, are very close to each other. In this way, the two doors presented in this text, which had an intensive use, fit in the context of the sacred historical soundscape of the city of Évora. This was one of the most important of Portugal during the second half of the sixteenth century, being the two objects treated here intimately connected to the musical history of this Alentejo urban centre.

Going, very briefly, the European Art History, some notably examples can be found of decorated doors in religious buildings in the Italian cities during the Renaissance. Besides guarding their interiors, these elements were covered with a strong symbolic character. As an example, one can mention the doors of the baptistery in Florence, made in the firs half of the sixteenth century by Lorenzo Ghiberti, depicting the life Christ in 21 panels, and another 8 depicting the Evangelists and the Fathers of the Church. Who walked through them certainly was not indifferent to these masterpieces which took 21 years to make, deserving from Michelangelo Buonarroti the epithet of “Doors of the Paradise”. Giorgio Vasari described them a century later as “undeniably perfect in every way and stand as the best masterpiece ever to be created”. These were only two of the numerous Western Art History figures who had the chance of witnessing the masterpieces of Ghiberti and leave their personal testimony. However, not every doors were so lucky.

With regard to the Évora context – significantly more modest that the Florentine artistic opulence – and, more specifically, to its Cathedral, two examples can be found of doors that arouse the attention in the musical context. Generally, decorated doors are rare, being more common the decoration of the porticos where they are placed, as is the case of the portico of Évora Cathedral, a fifteenth-century work attributed to Mestre Pero. Simpler and of difficult comparison with their Italian counterparts are the two Évora doors subject of the present text, with markedly more functionally characteristics. These, although representing a (musical) context and share the same functions, were located in places with very different dynamics and uses.

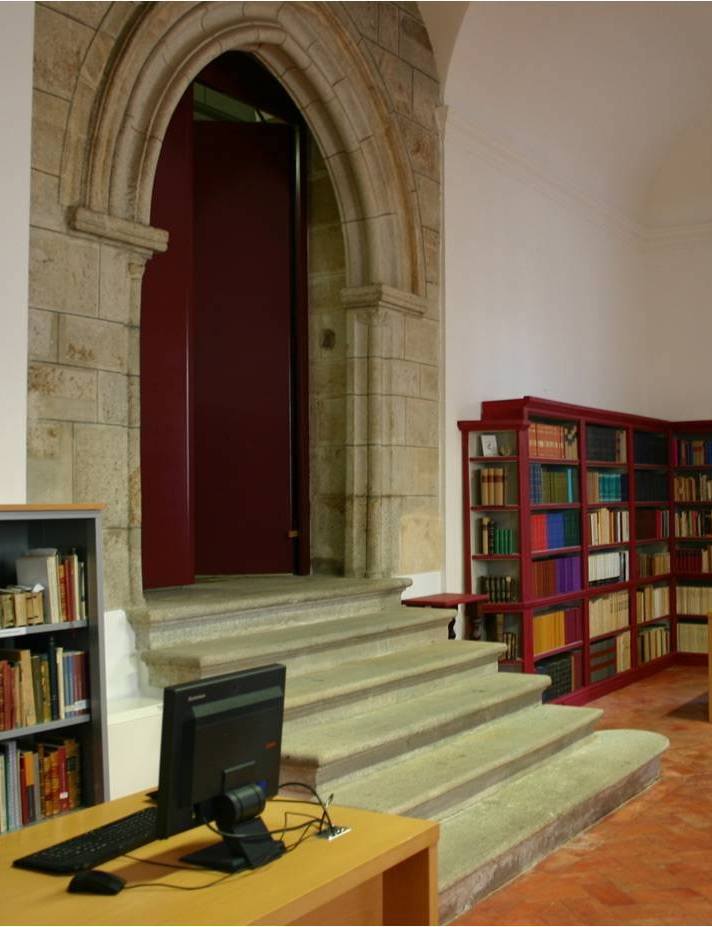

In Évora there are at least two cases, which, despite not being masterworks in terms of their decoration, hold a musical and cultural context that is seldom referred in Art History studies. The first of these examples is to be currently found in exhibition at the National Museum Frei Manuel do Cenáculo (Évora Museum) consisting of a set of two doors that belonged to the Barn of the Archbishop of Évora, in the building that is now the Évora Public Library.

The doors belonged to the South portico of the former barn next to the current building of the Public Library, which were described by the historian Gabriel Pereira at the beginning of the twentieth century. Pereira described the place and the surrounding area of the former Barn of the Archbishop, being interesting to notice in his description a picturesque tone still in the nineteenth-century style in an intention to transport the reader to the sixteenth century experience. At the time of the historian, the barn had a South door, which opened to an irregular-shaped yard, since it was divided by a terrace that crossed it obliquely in an inclined platform. To one side the high walls of the Cathedral were to be found and to the Eastern side, some houses, the Chapter’s barn and a portico, topped with a coat of arms, which led to the S. Miguel yard (and the Palace of the Counts of Basto, currently the Eugénio de Almeida Foundation). On the North side was located the so-called tower of Sertório (currently integrating the Évora Public Library), where at the time of Gabriel Pereira functioned a meteorological observatory, the barn, part of the Library’s building and a walkway supported by an arch which linked the building to the Archbishop’s Palace West of the yard. The barn had a porch whose arches were closed creating what Pereira called a vestibule, in which interior can be found the primitive entrance and the portico where the two doors were once placed.

Pereira proceeds describing in detail the said doors. He begins with the jambs which were made by oak boards, without any carving. Above these some iron bars were applied “illuminated, very decorated, with several drawings of noticeable execution”, with an iron sheet of about one millimetre of thickness. Twenty nails, with circular and creased heads, fix the boards to the crossbars, thirteen, with their heads carved in the shape of a flower are immediately down and the lower ones have several motifs. Pereira concludes that the doors present seven different friezes or stripes in carved iron. The historian further advances that in the upper stripe a second leaf was nailed above a previous one, suggesting the use of leftovers from other works establishing a connection to the Cathedral’s baptistery door, whose cyma is ornated with a stripe similar to one which is to be found in the barn door.

In terms of its musical context, the building where these doors were to be found housed during around a century and a half the Choirboys College of Évora Cathedral, an important musical learning institution founded by the Cardinal D. Henrique in 1552. The Jesuit priest Francisco da Fonseca referred, in his Évora Gloriosa, that the first building of the College had been in the old Cathedral, former house of the Senate and the Câmara clerk. However, due to the building ruin state, it was (on an unknown date) tranferred to the houses that existed behind the Chapter house, that is, the Archbishop’s barn. There lived fourteen (in certain times, increasing to twenty) choirboys until 8 May 1708, when the College was solemnly transferred for the wide building (nowadays the Cathedral’s Museum of Sacred Art) located next to the Gothic cloister of the Cathedral. This major work in the musical dynamic of the Cathedral was began by the Archbishop D. Luís da Silva, being finished during the time of the Archbishop D. Simão da Gama.

Sounding names of the Portuguese first half of the seventeenth century sacred music, such as Duarte Lobo, Fr. Manuel Cardoso or Filipe de Magalhães (this one, progressed in the Cathedral’s hierarchy, ascending to the post of singer and, later, as master of the Cloister), have passed, as choirboys (and some, later, as porcionários of the University), by the doors of the former barn. This first generation of boys of the Choirboys College as an autonomous institution was directed by one of the its first deans by the years of 1578 and 1580.

A second generation of choirboys that distinguished themselves in Portuguese and foreign religious institutions is headed by Estêvão de Brito, from Serpa, and Estêvão Lopes Morago, born in “Vallecas, in the Kingdom of Toledo”. These received the Bacharel degree in Arts from the University of Évora on 3 March 1596, what suggests that they must have remained in Évora more time than that usually spent by the choirboys in the College. The first was later chapel master in the cathedrals of Badajoz and Málaga, while the second held the same post in Viseu Cathedral, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Until the moving to the new building two generations of musicians might have passed through the former College building. One includes lesser-known names of the Évora music history (since only a few or no music output has survived to this day) as is the case of António Rodrigues Vilalva, Pedro da Fonseca Luzio or Bento Nunes Pegado. However, from the following generation a considerable number of musical works are known, as is the case of Francisco Martins or Diogo Dias Melgaz. The last one occupied the post of Dean of the College before its transfer to the new building, a date when Pedro Vaz Rego was already the dean, another name that is believed to also have studied at the former building as a choirboy.

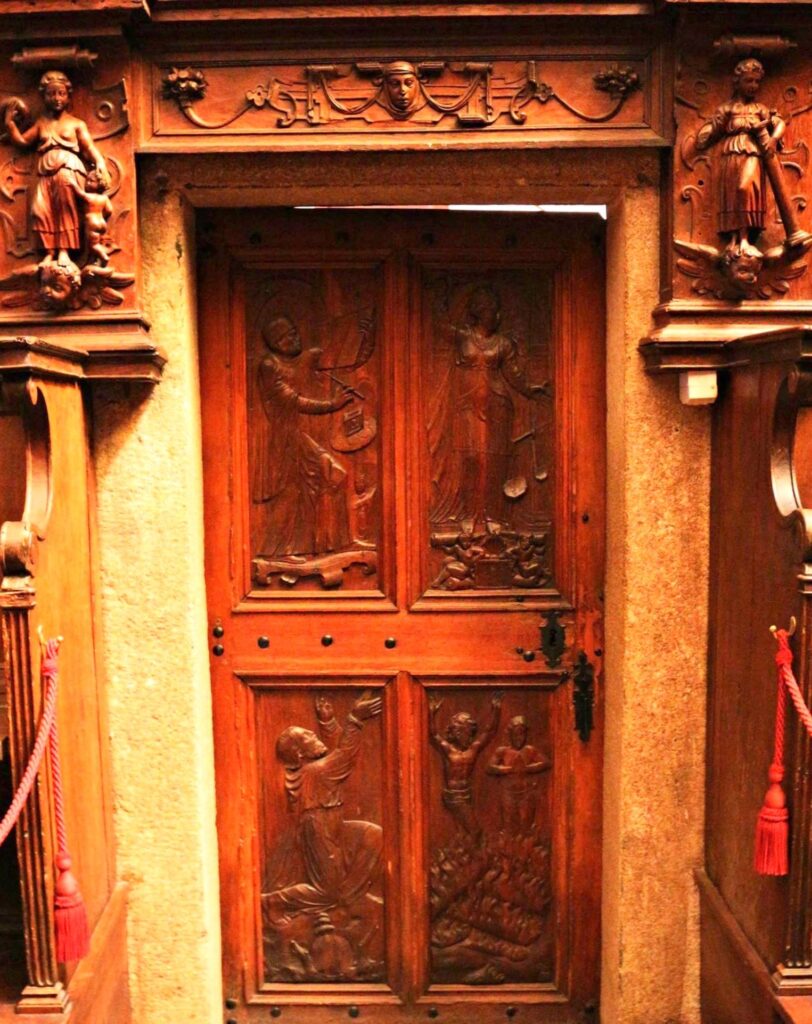

As previously mentioned, in the Cathedral it easily comes to the sight its imponent main entrance portico, a work inherited from Medieval time, as well as other secondary porticos in its exterior and interior. Not diminished their symbolism and importance, both in artistic and contextual terms, it can be found in this temple a second example concerning a door with an important musical context. This seems to be important to mention not only because of its artistic value but, again, also because of the associated musical context and by its artistic surrounding. We’re referring to the access door to the Évora Cathedral high choir.

Once more, it was Gabriel Pereira that noted its artistic importance, describing it in 1901 in the sixth volume of O Archeologo Português. The historian described the four panels that made the oak door “of a very perfect sculpture”, the upper left being depict the judge with the guilt book and, in the opposing side, the justice with a raised gladio in the right hand and the balance on the left. The lower panels depict a saint that begs for clemency on the left side and, in the opposing one, begging souls in the purifying fire with a masculine figure with arms up and a feminine with folded hands. Pereira adds a personal reading of the panels meaning stating that they would suggest the canons to pray and ask for forgiveness for the weak humanity when singing plainchant in the choir. Gabriel Pereira still adds that the door must have dated from the time of the installation of the choir stalls, dating from 1562.

This impressive work of wood carving holds two chronological indications referring the year 1562 as the one of its making. Incorporated in the stalls it is also found an historical organ, whose construction is attributed to Heitor Lobo, possibly a decade before, since it was at the service of the Cathedral between 1544 and 1553.

This door gives access to one of the most important music spaces of the Évora Cathedral. Besides this, the high choir, an almost forgotten element in current-day temples, had a striking symbology in the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century churches since it was in this space that there were celebrated the daily offices of each of the Canonic Hours. The high choir had its own doorman, in charge of watching over the access, keeping the door closed at every time between the several offices. It was also up to the Cathedral’s treasurer to keep the door of the high choir closed when the space was not being used.

If the door of the former Choirboys College played a more functional part in the daily routine of the individuals responsible for the musical service at the Cathedral, the door of the high choir, as mentioned above, had a more symbolic character as point of passage between the secular world and the religious and sacred one of that space where every day were musically celebrated the divine offices. Through this door and, maybe, contrary to the College one, passed names of great importance in the Portuguese musical history.

Mateus d’Aranda hadn’t seen the construction of the new stalls and organ of the high choir, since he left Évora in 1544, to occupy the post of Lente de Música at Coimbra University. His successors in the posts of chapel master and master of the Cloister certainly assisted to that refurbishment, the former singers Manuel Dias and Francisco Velez respectively. Manuel Dias died around the year of 1563, having been succeeded in the post by André Nunes. In the case of Francisco Velez, as Manuel Dias, his name appears in the list of singers of the chapel when the Cardinal D. Afonso visited the Cathedral in 1537. His career as master of the Cloister extended until the end of the 1570s, being succeeded by Manuel Mendes.

As happened in the College, also through the high choir of the Cathedral passed the generations of musicians previously mentioned as choirboys. These had the obligation of going to the lectern to sing the verses that the chapel master would point which, by that time, would be Cosme Delgado.

As summary, the present text intended to reflect about two artistic objects connected to the musical activity of Évora Cathedral in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, framing them in its musical context through the mention of some of the individuals that used them, by the way, important names in the Portuguese music history of the period. The two doors, despite objects of artistic value (one of them being relocated in a National Museum), represent also elements of everyday life with greater or lesser functionality having, in the case of the door of the high choir, a specific person to open and close it. In the case of the door of the Choirboys College (contrary to that of the choir, which is still in its origin place) it is as a testimony of a place whose initial functionality as a barn and, afterwards, as a College disappeared by the end of the seventeenth century and, thus, also its soundscape, meanwhile, also disappeared.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Alegria, J. A. (1997). O Colégio dos Moços do Coro da Sé de Évora. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Alvarenga, J. P. d’ (2015). On Performing Practices in Mid-to Late-Sixteenth Century Portuguese Church Music: The Cappella of Évora Cathedral. Early Music, 43(1), 3-21.

Chicó, M. (1946). Ferros Artísticos de Évora. A Cidade de Évora, 6, 95-96.

Henriques, L. (2018). A nova capela-mor da Catedral de Évora: Uma abordagem ao seu impacto na atividade musical de Pedro Vaz Rego e Ignácio António Celestino. Arte y Patrimonio, 3, 77-92.

Fonseca, F. da (1728). Evora Gloriosa. Epilogo Dos quatro Tomos da Evora Illustrada, que compoz o R. P. M. Manoel Fialo da Companhia de JESU. Na Officina Komarekiana.

Pereira, G. (1934). Estudos Diversos. Imprensa da Universidade.

Pereira, G. (1901). Porta do côro da Sé de Évora. O Archeologo Português, 6, 135-137.

Pessanha, J. (1901). Notas de Archeologia Artistica: 2. Ferreiros. O Archeologo Português, 6, 61-66.

FOOTNOTES

- This text is an English translation of a previously published Portuguese text in the magazine Glosas online (2020, January 20). ↩︎