The motet Cantantibus organis by Giovanni P. da Palestrina

❧

So much has been written about Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina’s compositions that it would be fruitless to follow the same approach to his music as many accomplished scholars have done so. So, in this text I’ll offer a personal perspective to a motet that has eluded me for some time.

As noted by John A. Rice one of the sixteenth-century music phenomena Palestrina absorbed was the influence of Netherlandish and French music throughout Italy. He recalls that the composer’s musical style, choice of genres and texts were shaped by the Franco-Flemish musical culture. One of these traditions was the association between Saint Cecilia and music, and the further association of the Saint as patron of the many societies of professional musicians in the Netherlands and France. Thus, many motets were composed in honour of Saint Cecilia by Franco-Flemish composers throughout the 1530s but only in 1563 it seemed to appear the first publication by an Italian composer, the motet Dum aurora finem by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. (Rice, 2006). Rice considers the Italianization of the Franco Flemish Caecilian motet tradition to be a Roman practice, although Venetian printers took part in its spreading. He referrers Palestrina Dum aurora finem and Cantantibus organis as the earliest Italian Cecilian settings (Rice, 2006). The composer seemed to be involved in several societies of professional musicians most notably the Compagnia dei Musici, organized in 1584 under the protection of Saint Gregory and Saint Cecilia.

Palestrina’s motet Cantantibus organis is divided into two partes (secunda pars being Biduanis ac triduanis) and is set for five voices (SATTB). As many of Palestrina’s five-voice motets I do admire how he works with this voice arrangement often creating micro-polychoral textures by dividing the voices in two choirs of high and low voices with the centre one acting as a common voice between both groups.

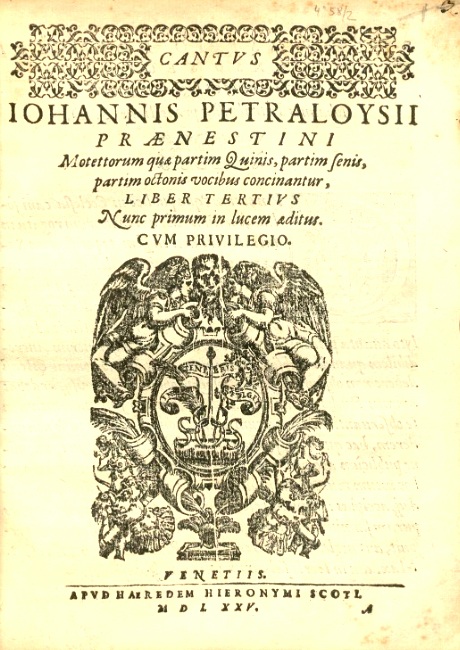

The motet was first published in Palestrina’s Motettorum quae partim quinis, partim senis, partim octois vocibus concinantur Liber Tertivs printed by the Venetian Scotto workshop in 1575. Besides the Cecilian motet, this collection presents 32 other works, several of which are widely known nowadays such as O bone Jesu (a 6), or Surge illuminare and Hodie Christus natus est (a 8). It features some of the best-known works by the Papal composer, some of them have been almost performed uninterruptedly since Palestrina’s time. The work makes use of the text for the first responsory at Matins for the feast of St. Cecilia, the second part of the motet using the text of the responsory verse.

The motet is a fine example of late sixteenth century imitation procedures. This can be heard in the opening segment with the sequence of voice entrances following the “classical” manner at a distance of a fifth, a fourth, and an octave interval. The initial imitation motive is very well carved in an ascending manner. By contrast, the second motive associated with the text “Cecilia virgo” is a descending one. He has the care of inserting this motive and its associated text further into the segment in order for the Saint’s name to be clearly heard. The first part of the motet is basically an example of how to create imitation points after imitation points. There isn’t any clear homophonic section throughout this part although in some moments the composer pairs voices in bicinia, usually with the intention of textual emphasis.

The second part, “Biduanis ac triduanis” opens with a long imitation, three of the voices (SAT) entering very close to each other and the remaining two (QB) only entering three breves later. This creates space in the lines, with a sort of introductory trio with the same text being repeated after the entry of the two voices. Again there is a predominance of imitation throughout this part, with the exception of several passages where Palestrina groups two or more voices, not in bicinia as in the first part, but in a two or three-part counterpoint, silencing the other voices that don´t take part by the use of rests or longer note values.

It is interesting to think that Palestrina might had a special care in the composition of this motet since it would be heard by his fellow composers of the Compagnia dei Musici during the Cecilian ceremonies. This could explain the level of music craftsmanship involved on each segment of the motet and the impressive balance achieved in terms of the imitative sections combined with more thin texture passages combining two or three voices for highlighting certain text passages.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Henriques, L. (Ed.) (2022). Giovanni P. da Palestrina: Cecilian Motets. Italian Sixteenth Century Polyphony Series 3. Évora: Canto Mensurable editions.

Rice, J. A. (2006). Palestrina’s Saint Cecilia Motets and the Missa Cantantibus Organis. https://sites.google.com/site/johnaricecv/palestrina-s-saint-cecilia-motets-and-the-missa-cantantibus-organis

Luís Henriques is a PhD candidate in Musicology at the University of Évora and researcher in training at the University of Évora branch of the Centre for the Study of Sociology and Musical Aesthetics, based at the NOVA-FCSH.