The Medieval Soundscape of Évora from a 17th-Century Perspective

Most of the published studies about the history of music in the Portuguese city of Évora have begin chronologically in the first decades of the sixteenth century onwards. This period corresponded to the activity of the Spanish chapel master Mateus d’Aranda at Évora Cathedral. The successors of Aranda both as chapel masters, singers, and instrumentalists, throughout the sixteenth century have been relatively well studied as well as the musical activity of the chapel.

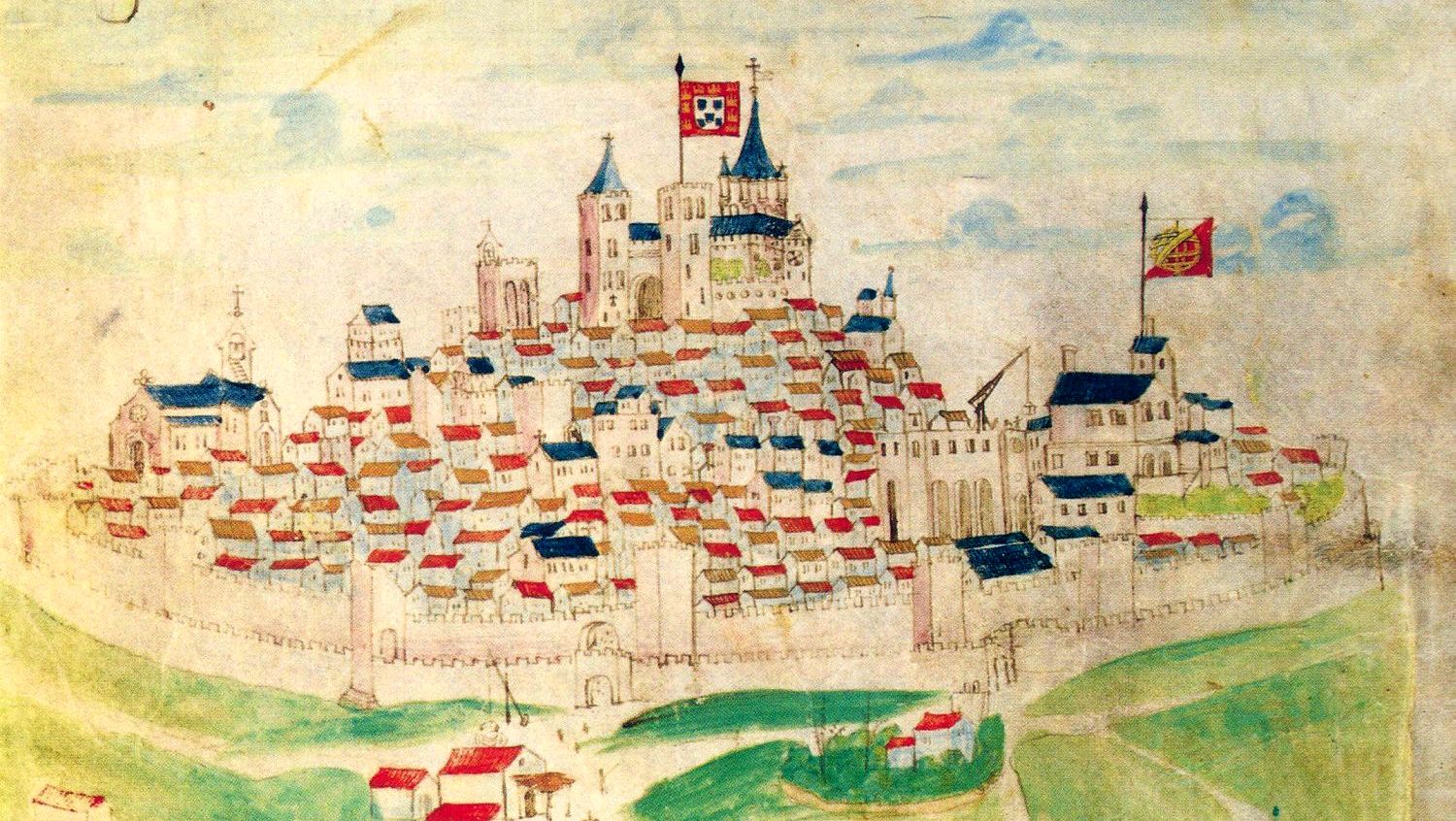

However, when going back to the fifteenth century and preceding centuries, both documentation and studies became scarcer. Most studies have focused on pre-Tridentine liturgical uses – notably, the so-called Use of Évora – and the relation between the Braga and Coimbra uses during the Middle Ages. But aside from the liturgical sources, how much do we know of the musical activity in Évora prior to the sixteenth century? If documentation from the period doesn’t provide many details about the institutions of Évora, in terms of their musical activity, the historical soundscapes studies present a new perspective on the understanding of how music would take place in these places as well as the interaction between the city’s various musical production centres and their liturgical contexts.

One perspective about the medieval period comes from two Jesuit writers of the transition from the seventeenth to the eighteenth centuries – Manuel Fialho and Francisco da Fonseca – and the views they present of the musical-liturgical activity in Évora. Both authors present the same view, with Francisco da Fonseca’s Evora gloriosa (printed in 1728) drawing much of its content from Manuel Fialho’s manuscript of Evora Illustrada, written in the last decade of the seventeenth century.

Manuel Fialho (1646-1718) is the author of Evora Illustrada, a manuscript that is now preserved at Évora Public Library (Cód. CXXX/1-11). Francisco da Fonseca (1668-1738) is the author of Evora gloriosa, printed in Rome in 1728. Both works complement each other, and several common readings can be taken from these writings.

The main institutions in Évora with musical activity during the medieval period mentioned by Fialho and Fonseca can be divided in three groups: the Cathedral, the collegiate, and the mendicant convents inside the city walls. Here we focus on the fourteenth century and first half of the fifteenth century and the religious institutions that could sustain a continuous musical activity such as the parochial churches or the convents.

In the case of the Cathedral and collegiates, that make the secular ecclesiastical group of the city, these institutions correspond to the same number of parishes in the medieval period. In these churches the so-called Uso or Costume of Évora would be in place as the liturgical orientation. This would be the case of the Cathedral and the collegiates of São Pedro, São Tiago, São Mamede and Santo Antão.

The Cathedral, dedicated to Our Lady of Assumption, was constructed during the last decades of the twelfth century. During the construction period the liturgical offices were celebrated in a house consecrated for that end (where is now located the Public Library). From this note we know that by that time there was already a musical-liturgical organization in the Cathedral that would include the singing of the daily offices, as well as the celebration of masses, with a group of singers specialized in those tasks. These would also include the celebration and singing of services from the chapel of masses instituted by testamentary dispositions.

The singing and celebration of chapel of masses was also one of the main activities for the beneficiaries or racioneiros of the collegiate churches. Here the daily offices were celebrated by a college of clergymen in the choir.

In the case of the Mendicant houses, the convent of São Francisco was founded in mid thirteenth century. The patrimony of the house was considerably augmented with donations by noblemen, which also included the institution of chapel of masses and the celebration of anniversaries. By the fifteenth century, the numerous Franciscan community included nine friars with choir obligation, which meant that they would dedicate most of their time singing in the choir.

The other Mendicant house, the convent of São Domingos, was founded in the end of the thirteenth century seeing its patrimony augment in the next years with a series of chapel institutions by relevant noblemen. The community was less numerous than in São Francisco but it would be capable of sustaining a considerable musical-liturgical activity since in 1299 it could send 13 friars to Barcelona to attend the provincial chapter that took place in that city.

Manuel Fialho and Francisco da Fonseca look at these institutions share a glimpse of their daily mostly-plainchant-orientated activity. Besides the daily singing of plainchant that could be listened throughout the city, the cathedral, the collegiates and the convents contributed to a musical soundscape, which would, in a great sense, be mixed with a lot of other sounds from the daily life of the city’s inhabitants.

[This text is a resume of a book chapter published in 2017. Download ![]() ]

]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALEGRIA, José A. A Prática e Ensino da Música nas Sés de Portugal (Da Reconquista a finais do Século XVI). Lisboa: Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa, 1985.

FONSECA, Francisco da. Evora gloriosa. Epilogo Dos quatro Tomos da Euora Illustrada. Roma: Na Officina Komarekiana, 1728.

HENRIQUES, Luís. “A paisagem sonora sacra de Évora na Idade Média: Leituras a partir dos escritos de Manuel Fialho e Francisco da Fonseca”. AZEVEDO, Tânia & LOURO, Maria Filomena (eds.). Ler a Idade Média Hoje. Fontes, Texto e Tradução. Braga: Edições Húmus/Centro de Estudos Humanísticos da Universidade do Minho, 2017, pp. 89-98.